WILLIAM H. PECK

1901 Orleans

Detroit, MI 48207-2718

ph: 313 393 8858

whpeck

DAVID ROBERTS, MASTER DRAFTSMAN

Some of the most appealing views and arresting images of the Nile Valley and the Holy Land ever captured in any medium were the work of the Scottish painter David Roberts. Although his drawings and paintings were created in the early nineteenth century they have been the subject of a relatively recent intense revival of interest; through the various methods of mass reproduction in the past few years they have become more widely known and consequently more popular than ever before. The lithographs based on Roberts’ drawings have been reproduced for a popular market in a wide range of media from elaborately illustrated books to posters, calendars and postcards. His views of the exotic Near East have become the standard by which the nineteenth century condition of the monuments and landscape has been judged. Today it is common to find popular publications of Roberts’ works with elaborate descriptive text in as many as five languages in the book shops and even on the news stands of Cairo and Jerusalem. These publications are certainly more compelling and presumably more attractive to the tourist than any comparable collection of modern photographs.

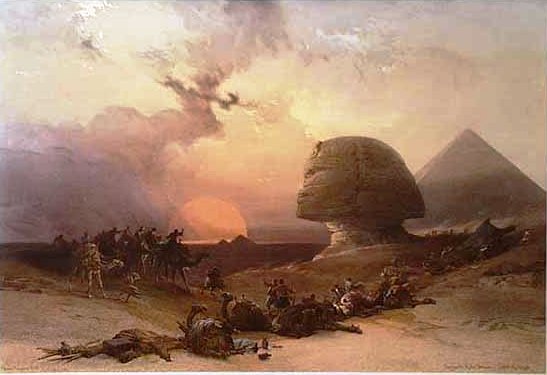

The Coming of the Sinoon

The quality that attracts us to his work is his perfect genius for capturing the salient qualities of the scene before him. With the eye of a romantic and the hand of a master draughtsman he combined the natural beauties of exotic places with the awesome character of ancient remains and ruins. These in turn, he combined and united with poignant vignettes of daily life.

Roberts sought to satisfy the appetite and curiosity of an English audience concerning newly discovered aspects of antiquity and he was fortunate that his works appeared at exactly the most opportune time for descriptive portrayals of the

Middle East. The abortive Eastern campaign of Bonaparte and his invasion of Egypt and the Holy Land at the beginning of the century had a number of lasting effects, not the least of which was that it set the stage for a large-scale influx of travelers and adventurers, literally following in the footsteps of the French revolutionary army. The first quarter of the nineteenth century saw more general interest and ready access to that part of the world, the arrival of more foreign travelers and adventurers from Europe than ever before, and the collection of Egyptian antiquities and artifacts on a unprecedented scale. Graphic representations of the sites and remains in the Nile valley and the Levant were in great demand. The market had been fueled a few decades earlier by the appearance of the popular engravings of Vivant Denon and the other French artists who illustrated the multi volumed Description de l’Egypt. An accomplished and imaginative painter like David Roberts was perfectly suited to satisfy the public demand while he could also take pride in his high degree of accuracy and the fact that he was the first English artist to illustrate the remains of ancient Egypt.

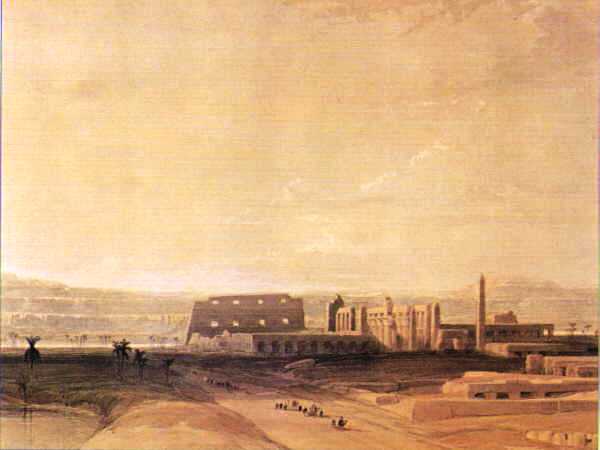

Luxor Temple

Luxor Temple

Roberts’ early career was not particularly unusual for his time. He was born in 1796, the son of a shoemaker and was apprenticed to an ornamental house painter named Bengo at an early age. When he completed his apprenticeship he soon found his real vocation as a theatrical scene painter, an occupation in which he quickly developed a high level of skill. For a time he toured with a traveling theatrical group in Scotland and the North of England and even appeared on stage in minor roles. In 1822, when his growing reputation had spread, he emigrated from Scotland to London at the age of 26. He was soon employed at most of the fashionable theatres of the time including the Old Vic and Drury Lane. Among his theatrical accomplishments that have been noted he was responsible for the sets for the first London performance of Mozart’s Abduction from the Seraglio at Convent Garden. Roberts was at the top of his craft, a rapid worker who was very much in demand for his abilities and his speed of execution. He had, however, artistic aspirations beyond that of a theatrical scene painter, so he soon began to work at the serious aspects of the "fine" arts. In 1824 he exhibited paintings at the British Institute and at the opening exhibition of the Society of British Artists, of which he was a founding member. As early as 1826 he was also able to exhibit at the Royal Academy. A View of Rouen Cathedral attracted a good deal of attention but he was not elected an Associate of the

Royal Academy until 1838. Roberts became a full Royal Academician two years later, signaling his complete acceptance by other professionals as an artist to be recognized. He attained a wide popularity in England and on the continent and one mark of distinction was that he continued to be an exhibitor at the Royal Academy every year from 1840 to 1864. His recognition and statue was such that he was appointed one of the commissioners for the Royal Exhibition of 1851. He received commissions for paintings directly from a variety of people ranging from Queen Victoria to Charles Dickens (who also happened to be his friend).

In 1838, the year of his elevation to the rank of ARA (Associate of the Royal Academy), he made his epochal trip to the

Near East on a journey which lasted eleven months. He spent considerable time in Cairo on three visits, evidenced by the number of detailed renderings of mosques, tombs and other architecture as well as the many scenes of daily life. He traveled the whole length of Egypt and farther south into Nubia than most people during his time. Alexandria, however, is represented by only a few compositions and the other monuments of the Delta not at all, in contrast to the lavish treatment accorded to the sites of Upper Egypt, especially in the Luxor area. When Roberts returned to England from Egypt, Nubia, Palestine and Syria, he brought back with him an estimated 272 detailed drawings as well as books filled with other, mainly smaller, sketches. With the help of his friend and fellow artist, the talented lithographer, Louis Haghe, Roberts turned much of this material into 247 plates for publication. The mathematics of this project are simple, Roberts made almost 300 drawings in eleven months, approximately 330 days, plus a panorama of Cairo and three full sketch books, a massive output for any draughtsman. When a reasonable amount of time is deducted for the vagaries of travel in remote countries in the early nineteenth century, indisposition or illness, as well as the preparation necessary for the actual work of recording the monuments, it almost defies the imagination to explain Roberts’ enormous productivity. The distinct possibility of illness, and the routine delays, dangers, and other diversions associated with travel in the Middle East in the 1830s undoubtedly served to complicate matters.

The Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings

Since most of Roberts' published lithographs as well as his oils and watercolors of Egypt are rich in the minute details of architecture and landscape (complete with some readable hieroglyphic inscriptions) they are obviously based on careful and direct observation. The wonder increases. There are few recognizable errors in the reproduction of the ancient monuments but some of these seem to be the result of artistic choice. A few random examples of deviation from reality will serve to suggest the artistic license Roberts employed. In one well known composition the orientation of the monuments suggests that the sun is rising (or setting) in the south, obviously positioned for dramatic effect. The drama is heightened by the inclusion of the less obvious vignette of a group of nomad bedowin struggling to save their black tent blown by the desert winds. In another lithograph the entrance to the Great Pyramid appears on the south, rather than the north side of the structure. One view of the Amun Temple at Karnak from the east includes the distant Nile at two different, disconnected, levels in the background.

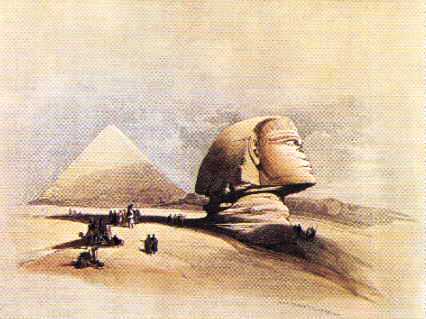

The Great Sphinx (slightly distorted)

These obvious errors in description of monuments and landscape are minor in the total body of work done in less than a year. However, the ability of an artist to be so precise in the delineation of the details of ruins and their settings, while maintaining such a level of rapid execution, might suggest the use of some mechanical drawing aid. The immediate possibility that suggests itself is the use of an optical instrument such as the camera lucida, a device particularly suited to the reproduction of complex architectural subjects and scenery, and one recently invented, or at least perfected, in Robert’s time. The camera lucida is a simple apparatus, easily constructed and eminently portable. In its least complicated manifestation it is little more than a piece of glass held at a fixed angle below the eye. The image of the subject is seen on the angled glass, but it is drawn on the paper below, in effect a tracing of an illusion. With the simplest version of the camera lucida the drawing is reversed, seen in a mirror image. The more developed form of the camera lucida employs a prism that serves to right the image and correct the reversal. It is entirely possible that Roberts employed the former, simpler, version because he was preparing his elaborate drawings for lithography, but use of the latter would have been equally possible.

The camera lucida was invented, or at least brought to its final practical form, by William Hyde Wollaston, the eminent nineteenth century English scientist. He was granted a patent in 1806 for "An instrument whereby any person may draw in perspective, or may Copy or Reduce any Print or Drawing". It was so-named on an analogy with the camera obscura, known and used by artists for centuries. Whereas the camera obscura, or "dark chamber” is descriptive of the device it names, "camera lucida" is something of a misnomer because a confined space is not part of the necessary attributes of the device. The noted artists who are known to have employed the camera lucida as an aid included painters and draughtsmen as diverse as the French academician Adolph Bougoreau, or the English landscape painters, Edward Lear, John Sell Cotman and Frederick Catherwood. Catherwood, incidentally, another artist who worked in the Middle East, actually makes a good comparison because, like Roberts, he is best known today for his somewhat romantic views of archaeological remains. His records of the early cultures of Central and South America are better known today than his views of the Middle East which predated them. In any case, the use of an optical aid greatly facilitated Catherwood”s field work which was often accomplished under difficult conditions. T. G. H. James, in his recent book on artist-travelers, Egypt Revealed, documents the use of the device by a number of early students of Egyptology including Robert Hay and George Alexander Hoskins, so it was certainly not unknown in

Egypt as a field aid in the time of David Roberts. David Hockney, the contemporary English artist, has recently advanced the provocative theory that the instrument or some variation of it was known and used by painters as early as the Renaissance. He argues that it did not really fall out of general use until the development of photography was well advanced. Karnak(The Nile at the left and far right are not on the same level)

Karnak(The Nile at the left and far right are not on the same level)

The argument against Roberts' use of the camera lucida is essentially based on lack of evidence to the contrary. There is simply no obvious reference to his employment of the device. Katharine Sim, who wrote what is probably the most complete biography of Roberts, said “…there has never been any mention of his using binoculars, or a camera lucida…” Sim was so puzzled by the seeming accuracy of Roberts’ vision that she consulted an ophthalmic optician for an opinion. He agreed that the ability to capture vivid and accurate detail in a brief exposure was very rare. The attempt to explain Roberts' work as enabled or facilitated by a device like the camera lucida must rest on three considerations: 1) The lithographs often have the appearance of a traced drawing. This in itself is admittedly not a particularly conclusive argument and is based on a subjective esthetic judgment. One might argue that this is possibly attributable to the translation of Robert's original work to the medium of lithography by another hand. 2) The sheer number of works produced by Roberts on his Middle Eastern trip, when measured against the available time for work in the field, suggests that few, if any, draughtsmen or artists could have produced such quantity while maintaining the high quality, accuracy, and attention to extremely complex detail. 3) The recognition that there exists in some of the lithographs a certain degree of visual distortion possibly the result of the use of a device incorporating a lens or necessitating a fixed viewpoint. One view of the Great Sphinx at Giza has the head tilted upward at a remarkable angle with an effect almost suggesting a “fish-eye” lens.

Aside from the question of the use of the Camera Lucida an analysis of many of Roberts' prints leads to a fair indication of his working methods and sequence of composition. It is evident after inspection of the lithographs that Roberts combined overall views of the monuments and the landscape with separately prepared sketches of the picturesque local inhabitants in a regular manner that becomes a hallmark of his characteristic style. His standard formula or working method consisted of the representation of the carefully delineated monument or locale first, with the secondary insertion of “set-groups” of people and animals, probably derived from the smaller sketches in his notebooks. These additions of local color were regularly used to provide a focus of interest in the composition as well as serve to increase the sense of scale. Most often these set-groups are composed of local people in typically picturesque costume, but occasionally they include portrayals of European travelers. Without the inclusion of these images of individuals and groups the sense of the vast size of the monuments and the depth of the landscape would be hardly be as effective.

The suggested use of the camera lucida and the cumulative construction of the compositions in no way lessens the quality of Roberts” work. However they were accomplished, David Roberts created a view of Egypt and the Holy Land

that is somehow timeless. There is a clarity in his line drawing that is instantly appealing and visually satisfying. Even when he intentionally distorted the arrangement of a ruined monument or changed the physical orientation for artistic effect, his skillful hand and his careful attention to detail still created a vivid record of the antiquities as they were at the mid-nineteenth century. Roberts’ contemporary, the famous art critic, John Ruskin, singled out Roberts as the “only one professedly architectural draughtsman of note” among English painters in his time. He further described Roberts' work as “dependant on no unintelligible, lines or blots, or substitute types,” suggesting the accuracy of Roberts' renderings. Ruskin was generally full of praise for Roberts and only regretted that he had not made full effect of the uses of color in his larger paintings in oil.

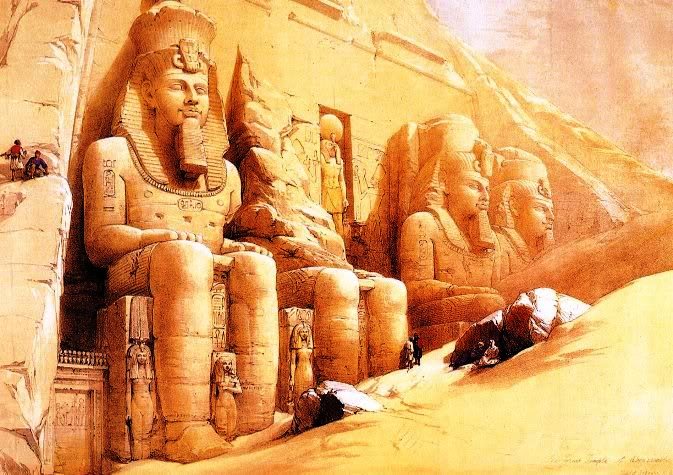

Abu Simbel

Abu Simbel

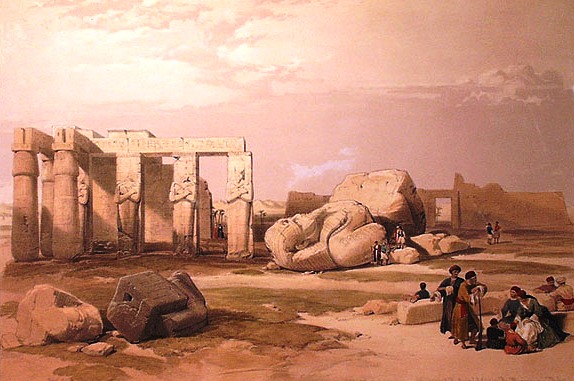

The images that David Roberts made of the monuments of Egypt and the Holy Land endure as a lasting record of the state of things as they appeared in the 1830s. Compared to the pioneer photographs of the mid-nineteenth century they are so fresh and revealing today that one has to recall that they were created more than a century and a half ago. They provided generations of “armchair” travelers with a vicarious experience and they continue to whet our appetites for the reality. They recall the memory of a grandeur and antiquity long passed, seen at a time when it had not been overrun by tourists or spoiled by modern progress. The Ramesseum from a distance

The Ramesseum from a distance

Further Reading

Note: There are many illustrated books on Roberts and on early travelers that include Roberts prints. The color is not always accurate in many of them but this is in part due to some variation in the hand coloring process in the original published lithographs as well as the reproduction technique used. For a further study of Roberts the following books are recommended:

- Katherine Sim, David Roberts R.A. :1796-1864 (London: Quartet Books, 1984) Probably the best biography of Roberts.

- Fabio Bourbon, Ancient Egypt: Lithographs by David Roberts, R. A. (Editions White Star, 1997) Large format with good illustrations of the lithographs.

- (Helen Guiterman), David Roberts: From an Antique Land (BLA Publishing, 1989) Illustrations and excerpts from Roberts’ travel notebooks.

- John H. Hammond, Jill Austin, The Camera Lucida in Art and Science (Bristol: Adam Hilger, 1987) Technical discussion of the Camera Lucida.

William H. Peck

The Ramesseum

The Ramesseum

This article originally appeared in KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt, Vol. 12, No. 2, Summer, 2001 as:

Windows on Antiquity: Egypt in the Late 1830s Captured for All Time in the Works of Scottish Artist David Roberts

(there were more illustrations in the original publication)

N. B. Since this article was written the author has re-examined many of the Roberts Egyptian scenes with an idea of determining how much the use of human figures was included to establish scale. It has become apparent that Roberts, in his inclusion of human images, constantly reduced their size in proportion to their context with the consequent effect of making buildings and monuments appear larger than actuality. In some case, such as Abu Simbel, and the Temple of Dandur, this has made the monument appear much more imposing than it is in reality.

Copyright 2009 William H. Peck. All rights reserved.

1901 Orleans

Detroit, MI 48207-2718

ph: 313 393 8858

whpeck